The Hindu Editorial Analysis

9 July 2025

The dark signs of restricted or selective franchise

(Source – The Hindu, International Edition – Page No. – 8)

Topic: GS 2: Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation

Context

A major disruption of India’s electoral democracy is unfolding in Bihar, risking the creation of millions of second-class, insecure citizens.

Introduction

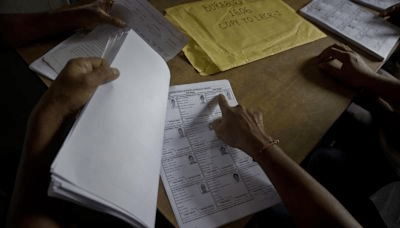

We are now in the second week since the sudden start of the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in Bihar, which began on June 24, 2025. Many people know this is happening after a gap of over 20 years, but that’s only half the truth. This time, the SIR is very different. It involves a complete rebuilding of the voter list, based on the documents submitted by those who want to register as voters.

Revisiting trauma

- The Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in Bihar began suddenly on June 24, 2025.

- It has brought back memories of demonetisation (2016) due to its lack of transparency and poor planning.

- People have started calling it ‘votebandi’, comparing it with ‘notebandi’.

- It also resembles the NRC exercise in Assam, which was long, monitored by the Supreme Court, and took 6 years.

Bihar vs Assam: A Comparison

| Aspect | NRC in Assam | SIR in Bihar |

| Duration | 6 years | 1 month |

| Population covered | 33 million applicants | 50 million voters |

| Supervision | Supreme Court | No judicial supervision |

| Exclusions | 2 million people | Potentially large-scale, unclear numbers |

| Documents Required | Varied, with legal aid provisions | 11 rare documents, hard to obtain |

| Timing | Managed and phased | During monsoon and migration peak |

Harsh Documentation Requirements

- The Election Commission of India (ECI) has asked for 11 enabling documents to prove voter eligibility.

- Common documents like Aadhaar, voter card, ration card, etc., are not accepted.

- Instead, people are asked to provide rare items like:

| Unaccepted Documents | Accepted Documents |

| Aadhaar card | Birth certificate |

| Voter ID | Matriculation certificate |

| Ration card | Land or house ownership record |

| Driving licence | Caste certificate |

| Job card (MGNREGA) | Passport |

- Most common people in Bihar do not possess these rare documents.

Migrant Workers Face the Worst Impact

- High migration from Bihar means many residents live or work outside the State.

- These people may be removed from the voter list if they are seen as not ‘ordinarily residing’ in Bihar.

- During the COVID lockdown in 2020, thousands of Bihari migrants returned home on foot — now, many of them may lose voting rights.

Risk of Mass Disenfranchisement

- Migrants are being labelled as outsiders in their own State.

- Their informal settlements are being demolished in places like Delhi, and now, they risk being erased from electoral rolls in Bihar.

- The fear of mass disenfranchisement is very real.

- The ECI’s electoral roll in Maharashtra recently showed a population larger than the actual adult population.

- With no clear explanation for this statistical error, is the ECI now trying to balance the numbers by cutting voters in Bihar?

A fundamental disruption

- The Election Commission of India (ECI) has stated that the Bihar SIR model will be replicated across the country in the coming months.

- This marks a major disruption in the way electoral democracy has been practised in India since the Constitutionwas adopted and the Representation of the People Act, 1951 was enacted.

- The current ‘votebandi’ exercise in Bihar has created chaos and raised serious concerns about voter rights.

- There are three key warning signals for India’s fragile democracy emerging from this exercise.

- The responsibility of proving citizenship is now being shifted from the State to the individual citizen.

- The empowered voter is now being treated as a suspect, and must prove their eligibility through rare documents.

- This reverses the basic principle of natural justice — where a person is innocent until proven guilty.

- The process converts the default voter into a doubtful citizen, placing the burden of proof on the poor and document-deficient population.

- If this approach is applied nationwide, it could become a major disaster for India’s democratic system.

A disenfranchised category

- The Election Commission of India (ECI) says that citizenship is a constitutional requirement for being a voter.

- The current Special Intensive Revision (SIR) is described as merely a verification process to check voter eligibility.

- People whose names were on the 2003 electoral roll are being automatically treated as Indian citizens.

- Everyone else must now prove their citizenship through documents, even if they have lived and voted in India before.

- This could lead to the creation of a new class of disenfranchised citizens — people who are legally citizens but are not allowed to vote.

- These individuals would be treated as second-grade citizens, lacking the security and rights of fully empowered voters.

- Such people would remain dependent on the state or the majority class to exercise basic rights.

- The impact is alarming — it risks undermining democracy and increasing social divisions.

- Universal adult franchise has been the foundation of India’s democracy and Constitution.

- In many other countries, marginalised groups had to struggle for decades to gain equal voting rights — India risks moving backward on that front.

Conclusion

In India, we got the right to vote for everyone at once when we gained freedom and adopted the Constitution. It was not given in parts or slowly. But now, in Bihar, by asking people to submit their educational certificates and property papers, are we moving towards a system where voting rights become limited or selective again?