The Hindu Editorial Analysis

30 August 2025

Detoxifying India’s entrance examination system

(Source – The Hindu, International Edition – Page No. – 8)

Topic :GS 2: Issues relating to development and management of Social Sector/Services relating to Health, Education

Context

India faces a choice: maintain the stressful competition that impacts youth or implement a framework of equity and justice in admissions.

Introduction

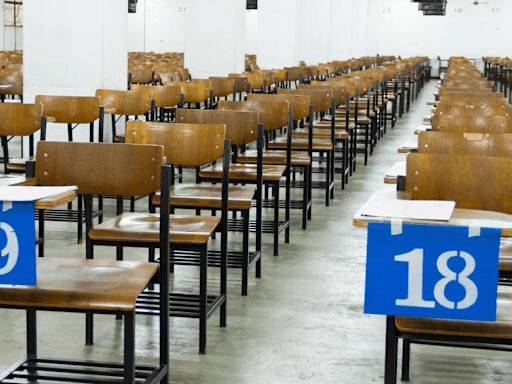

Every year, nearly 70 lakh students in India compete for undergraduate seats through entrance examinations such as the JEE, NEET, CUET, and CLAT. With a fixed number of seats, the competition is intense, giving rise to a thriving coaching industry and a culture of relentless pressure. Recent issues, including branch closures, financial misconduct at a major JEE coaching centre, an Enforcement Directorate raid, and student suicides, underscore a broken system. It is time to rethink undergraduate admissions, focusing on fairness, equity, and student well-being.

The coaching crisis and its toll

- Scale of aspirants: 15 lakh students compete for roughly 18,000 IIT seats, creating intense competition.

- Coaching industry: Centres charge ₹6-7 lakh for two-year programmes; students start as young as 14 years.

- Excessive workload: Students solve complex problems from books like Irodov and Krotov, far beyond B.Tech requirements.

- Psychological effects: The rat race causes stress, depression, and alienation, impacting peer bonding and normal adolescence.

- Regulatory attempts: Some state governments have tried to regulate coaching centres, but the root issue is the entrance exam system.

- Unreasonable distinctions: Differentiating students with 91% vs 97% in Class 12 or 99.9 percentile in JEE is unnecessary; a 70%-80% score in Physics, Chemistry, and Mathematics is sufficient for B.Tech.

- False hierarchy: The system favors those who can afford coaching, sidelines capable students, and worsens urban-rural, gender, and regional disparities.

- Illusory meritocracy: Wealthier families are privileged, creating a toxic obsession with superiority, ignoring luck and privilege.

- Global perspective: Philosopher Michael Sandel recommends lotteries for elite admissions (e.g., Stanford, Harvard) to address meritocratic excess.

The Dutch lottery and beyond

- Learning from the Netherlands

- The Netherlands uses a weighted lottery for medical school admissions, first introduced in 1972 and reinstated in 2023.

- Applicants meeting a minimum academic threshold enter a lottery; higher grades improve odds.

- This system reduces bias, promotes diversity, and eases pressure, addressing the limitations of overly precise metrics.

- Demonstrates that lotteries are viable when capacity is limited, supporting Sandel’s critique of meritocratic excess.

- China’s “Double Reduction” Policy

- Introduced in 2021, the policy banned for-profit tutoring for school subjects.

- Coaching was nationalized overnight to reduce financial burdens, address inequalities, and protect student well-being.

- Tackles challenges similar to India’s unregulated coaching industry and its negative impact on youth.

- Proposed Admissions Approach for India

- Simplify admissions and trust the school system.

- Use Class 12 board examinations as the benchmark for B.Tech readiness.

- Set a minimum eligibility threshold (e.g., 80% in Physics, Chemistry, and Mathematics).

- Group students into categories (90%+, 80%-90%) and allocate seats via a weighted lottery, incorporating gender, regional, and rural reservations.

- Higher grades improve odds but ensure fair chances for all, reducing cut-throat competition.

- Enhancing Equity and Diversity

- Reserve 50% of IIT seats for rural students educated in government schools, promoting social mobility.

- If entrance exams persist, coaching should be banned or nationalized, with free online resources provided.

- Introduce annual IIT student exchange programmes to promote national integration and exposure to diverse cultures.

- Encourage professor transfers between IITs to maintain uniform academic standards and dismantle artificial hierarchies.

Conclusion

Scrapping undergraduate entrance examinations in favor of a lottery-based system would liberate students from the coaching treadmill, allowing them to focus on school, sports, and holistic growth. It would lower financial barriers, giving every qualified student, irrespective of wealth or privilege, a fair chance at top institutions. Most importantly, it would let youth be youth, instead of turning them into machines chasing percentiles at a tender age. India’s education system stands at a crossroads: it can either continue a toxic race that harms students and society, or embrace fairness, sanity, egalitarianism, and equal opportunity. The choice is unmistakably clear.